Photographer Visits Creepy Cryogenic Chamber Where 200 Bodies Are Stored

![]()

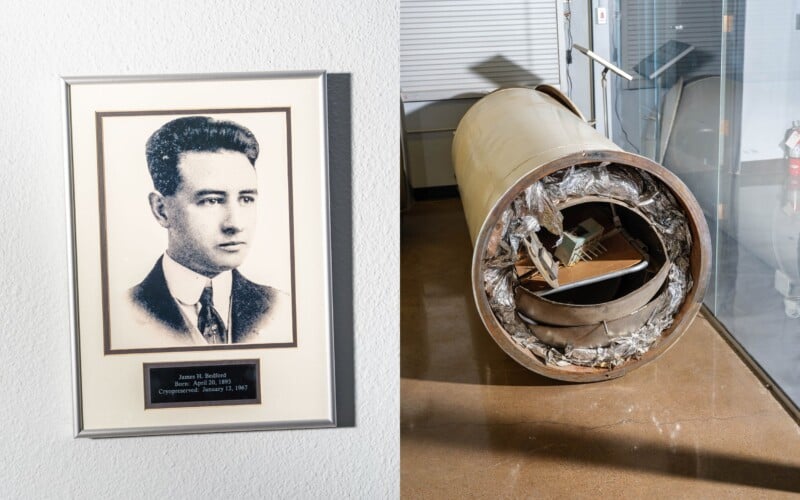

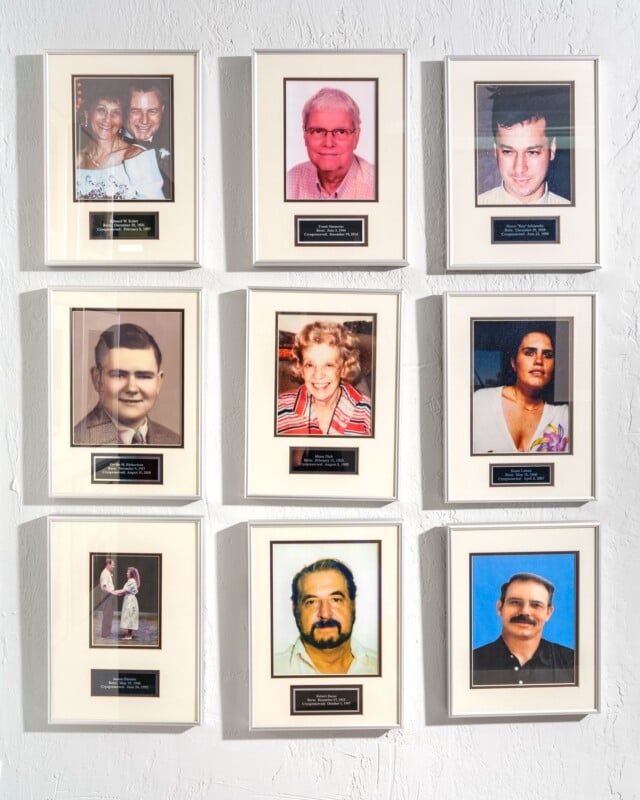

A photographer was given special access to a cryogenics facility in Scottsdale, Arizona that preserves over 200 human bodies and heads.

Alastair Philip Wiper spent two days at the Alcor Life Extension Foundation’s headquarters which he tells PetaPixel was both exciting and weird.

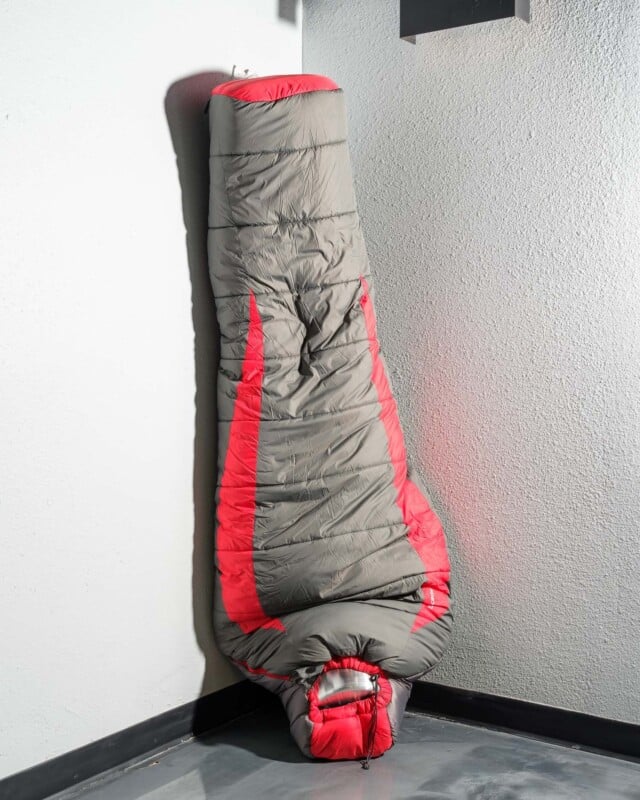

“It was amazing to be in the Patient Care Bay, surrounded by these dewars that look like something from a brewery, but are full of hundreds of dead bodies,” the photographer says.

The dewars are specialized containers that hold cryopreserved cadavers at minus 321 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 196 degrees Celsius).

“It’s a fascinating mix of science fiction and dead bodies,” says Wiper who adds that he is “really attracted to subjects that are wacky or taboo, or something other people might think was unpleasant.”

Wiper got Bloomberg Businessweek on board with the story but he says Alcor was keen to show the world what they are doing. Co-chief executive officer of Alcor, James Arrowood, tells Businessweek that he sees cryogenics as scientific research rather than a bizarre science fiction plot.

“I know what happens if I choose cremation,” Arrowood says. “I know what happens if I choose burial. I also know what the loss is to the science.”

Arrowood points to the brain of Albert Einstein which was removed for study and cut into pieces but there was no way of preserving it.

“Einstein’s brain is all over the world in little chunks,” he says. “And you can never get that data back.”

Photographing Inside a Cryogenic Chamber

Wiper went for a simple one-strobe setup with his camera on a tripod operated via a shutter release. “I want the images to be vibrant and alive (no pun intended!),” he says.

The photographer says on one of the days he was there the facility had a body coming in that was to be neuro-preserved, meaning the head would be removed and put into storage.

“I think it came from California, and a team had been there to collect the body in the special van they have, keeping everything in the right condition until they got it to their facility,” he says.

“Everybody was very excited and nervy — it doesn’t happen every day and it is a very complicated procedure with a lot of responsibility — they don’t want to mess it up.”

Unfortunately, Wiper wasn’t allowed to photograph that and there were also a few patients he wasn’t allowed to show either.

Getting Your Body Cryogenically Preserved

Wiper says he has no plans to get himself preserved, but if he did it would set him back $200,000 for his entire body or $80,000 for just his head. Then there’s a monthly membership fee of £100. Businessweek noted that most of the members cover the cost by designating Alcor as the beneficiary of their life insurance policies.

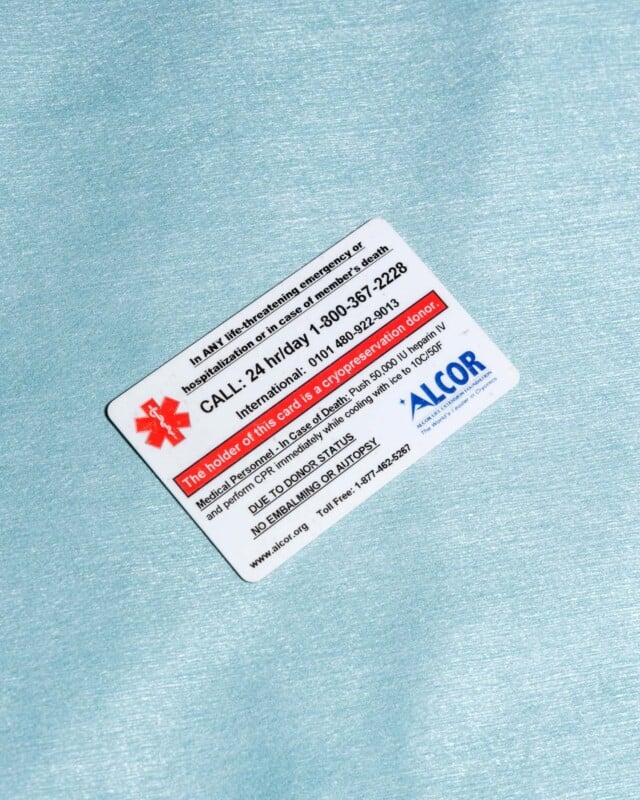

Living members wear medical alert bracelets to instruct hospitals to contact Alcor in the event of a life-threatening emergency. If the members die, their bodily fluids are replaced with special solutions that won’t become ice when the corpse is cooled to a chilly minus 321 degrees Fahrenheit.

More of Wiper’s work can be found on his website and Instagram.

Image credits: Photographs by Alastair Philip Wiper.